Outputs

What is a transaction output?

The bitcoin transaction system involves sending and receiving whole "batches" of bitcoins, called outputs.

Simple enough, but the only way to really understand how outputs work is to look at a few example transactions.

Where do outputs come from?

Let's begin this explanation of transaction outputs with the birth of a fresh batch of bitcoins…

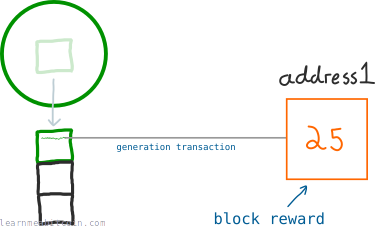

You are mining bitcoins on your own. By some miracle, you have managed to mine a block of transactions and earn yourself a block reward.

Every miner includes their own address at the top of each block, so if they manage to mine the block, the block reward can be sent to their address. This is claimed via a coinbase transaction (or as it used to be referred to, the "generation transaction").

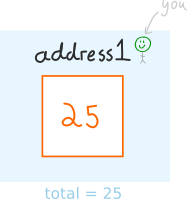

So this is the current state of your bitcoin address:

The block reward was 25 BTC when I first wrote this article.

Naturally, your first instinct is to celebrate. So let's use 1 of these bitcoins to buy some beer.

Beer.

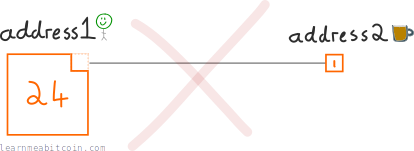

Now, your other first instinct would be to chip off 1 of these bitcoins (from the block reward) to pay for this beer. This would make sense, but it's not quite how transactions work.

Not quite. And that's one expensive beer.

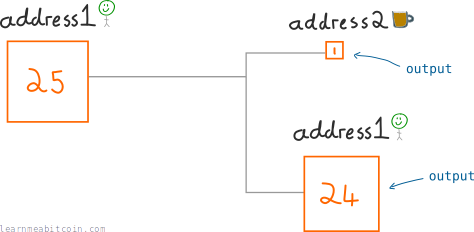

Instead, we have to send the entire batch of 25 bitcoins in the transaction.

But to make sure we don't spend all 25 bitcoins in a "1 bitcoin" payment, we split the batch up and send it to two destinations:

- To the beer shop as payment

- Back to our own address as change

The newly created batches are called outputs.

It's a bit of an around-the-houses way of doing it, but it achieves the same end-result.

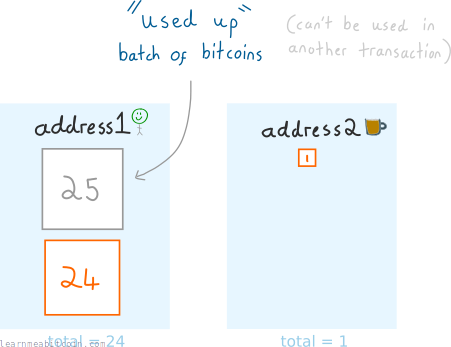

Anyway, this is what the bitcoin addresses look like after the transaction:

The beer shop has a new batch of 1 bitcoin, and we've sent ourselves a new batch of 24 bitcoins (as change). The original batch of 25 bitcoins has now been "used up" and can't be spent again.

So effectively it's as though we took 1 bitcoin from our address and sent it to another address… but now we know what's really going on under the hood.

The reason transactions use this "outputs" system is because it's an easy way of constructing payments from a programming perspective.

How do you spend multiple outputs in a transaction?

Okay, from now on we're going to use the word output instead of "batch".

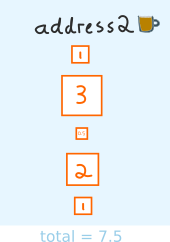

Anyway, a few days have passed since the beer shop sold us that beer. And judging by the current state of their bitcoin address, the beer business is booming:

The beer shop has received four new payments since we bought our beer.

But as we all know, beer doesn't grow on trees. So the beer shop is on the lookout for a brand-new beer machine.

This is what my friends call me on nights out.

Oh look, a lovely beer machine for the low, low price of 4.2 bitcoins.

Let's buy it…

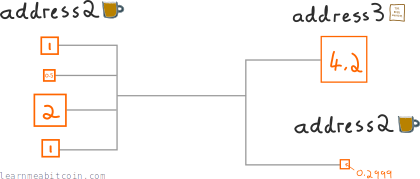

Constructing the transaction for the beer machine.

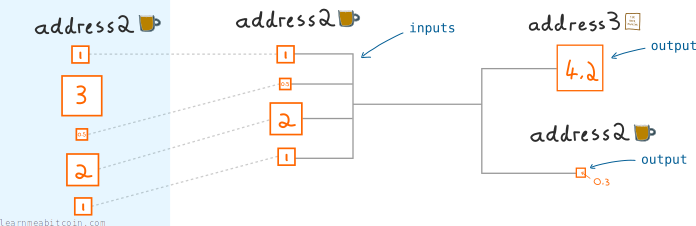

Alright, I realize I've just cranked the diagram up a few notches on this one, but it's not too difficult to understand:

- The beer shop doesn't have a single output at their address to cover the cost of the beer machine (4.2 BTC). So instead, we gather a handful of outputs together to get a total greater than 4.2 BTC.

- When we construct a transaction, the outputs we gather for spending are referred to as the transaction inputs.

- Using the total input amount of 4.5 BTC, the beer shop creates two new outputs of 4.2 BTC and 0.3 BTC.

When you're spending an output in a transaction, it's referred to as an input.

And here's the state of the beer shop's bitcoin address after the transaction:

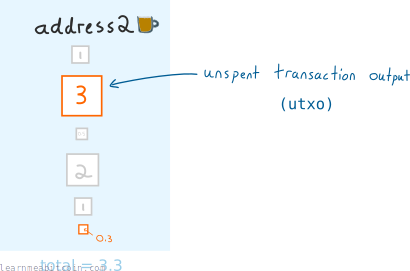

The beer shop has used up 4 outputs, and has one new 0.3 BTC output (from the change).

Once again, the outputs that were used as inputs have been "spent", and can't be used again.

The "unspent" outputs, however, are still good for spending, so we call these the unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs).

The balance of an address is the sum of the address's UTXOs.

Where do transaction fees come from?

Ah yes, we've not included a transaction fee in either of the last two transactions.

Without a transaction fee, those two transactions will probably take a while to get included in a block (if ever). This is because a transaction fee gives your transaction priority.

You see, transaction fees are picked up by miners when they mine a block. So if there are lots of transactions waiting in the memory pool, adding a transaction fee provides an incentive for miners to include your transaction in their next block.

Anyhow, pretend we didn't send that last transaction into the network, and let's add a transaction fee to it:

Okay, so where the hell is the output for the transaction fee? Well, there isn't one. But look at the size of the outputs.

The total of the outputs is less than the total of the inputs, which means that there are some remaining bitcoins that aren't being used up. This "left over" amount is the transaction fee.

And that's all transaction fees are – the remainder of a transaction.

The amount that's left over in a transaction always gets picked up by a miner. So if you manually constructed a transaction and forgot to create a change output for yourself, the miner would pick up the amount you left behind, no matter how much it is. This is not something to worry about if you're using a wallet to construct your transactions for you though, as they will always take care of the change for you.