Mining

Adding new blocks to the blockchain

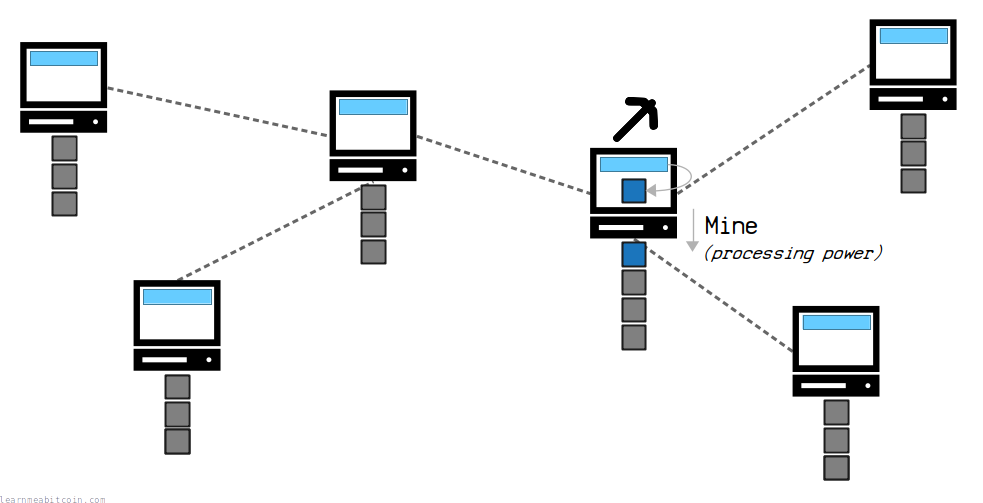

Mining is the process of trying to add a new block of transactions on to the blockchain.

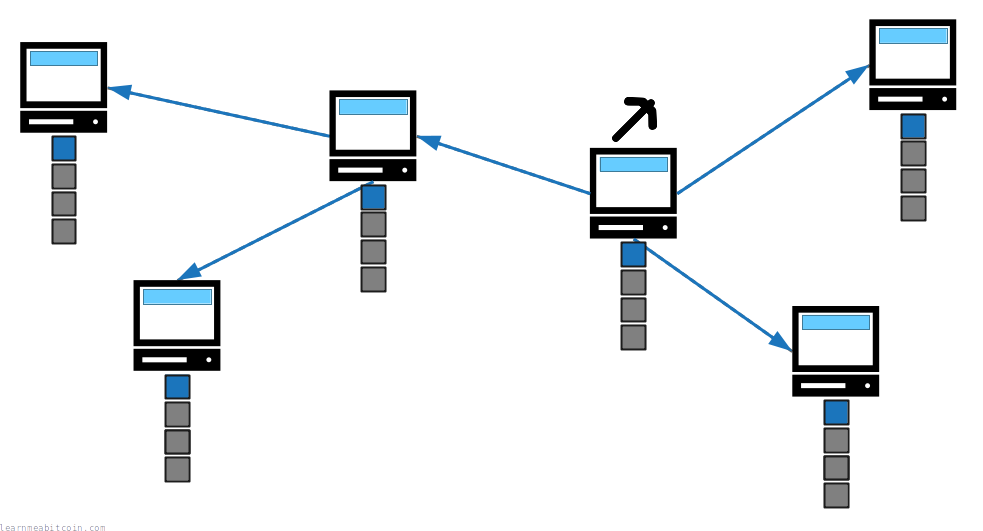

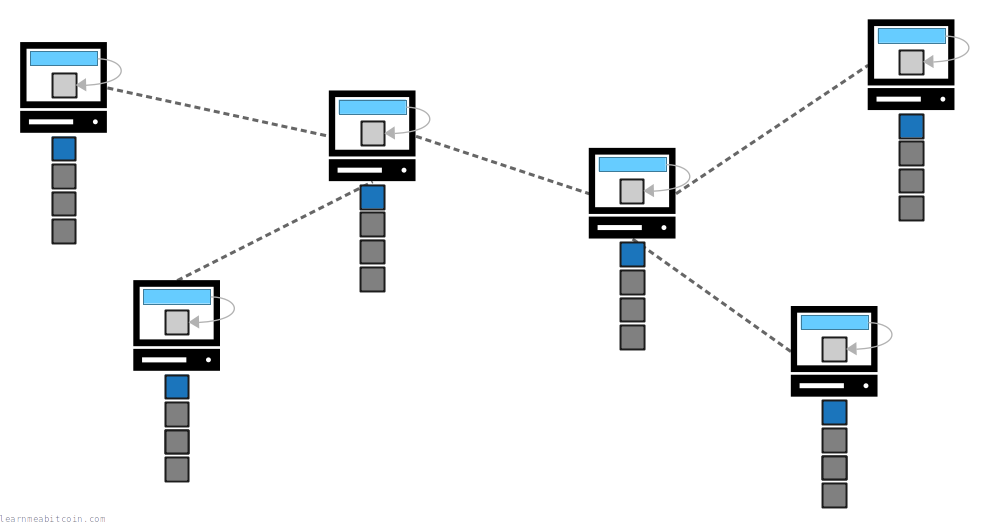

It's a network-wide competition where any node on the network can work to try and add the next block on to the chain.

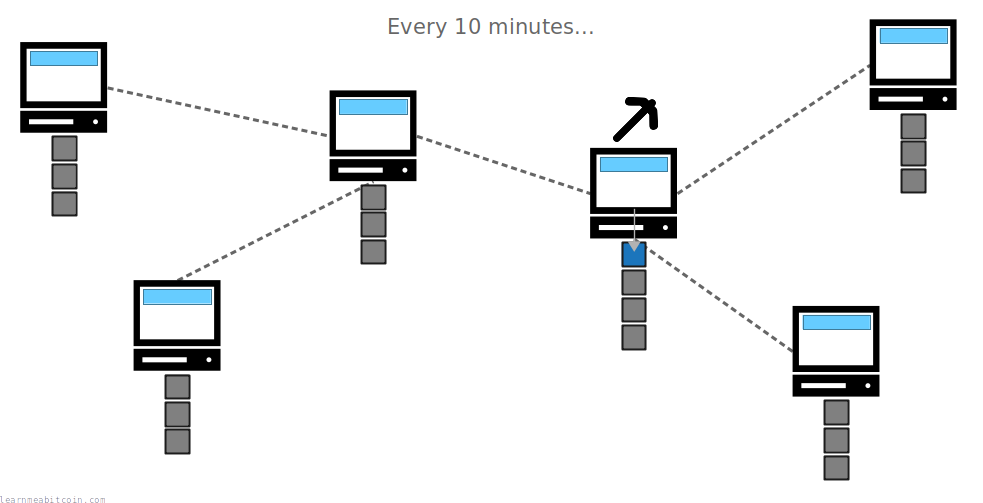

When a new block is mined, it gets broadcast across the network, where each node independently verifies and adds it on to their blockchain.

After adding the new block, each mining node restarts the process to try to build on top of this new block in the chain. As a result, the blockchain is regularly updated thanks to a collaborative effort of nodes across the network.

The system is designed so that a new block is mined once every 10 minutes on average.

Method

How does mining work?

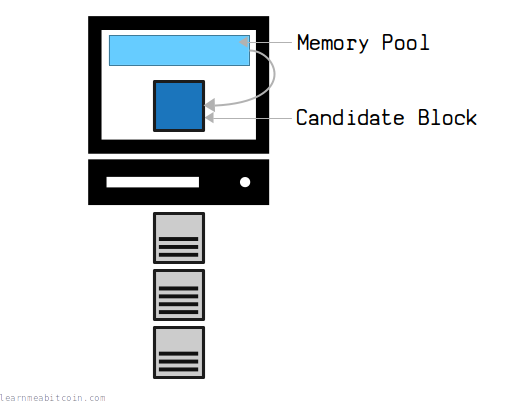

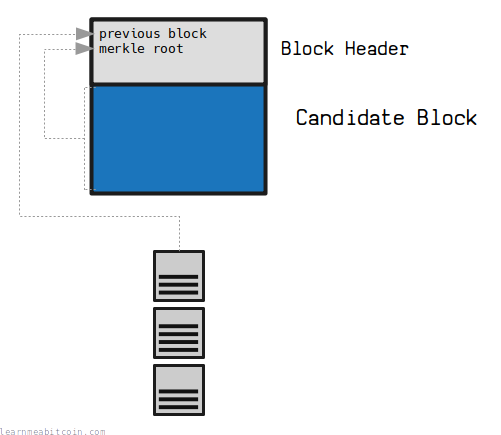

The mining process begins by filling a candidate block with transactions from your node's memory pool.

This candidate block is what we're going to try and mine on to our blockchain (and then send to everyone else so they can add it to their blockchain too).

Next we construct a block header for this candidate block. This is basically a short summary of all of the data inside the block, which includes a reference to an existing block in the blockchain that we want to build on.

Now we are ready to start mining this block.

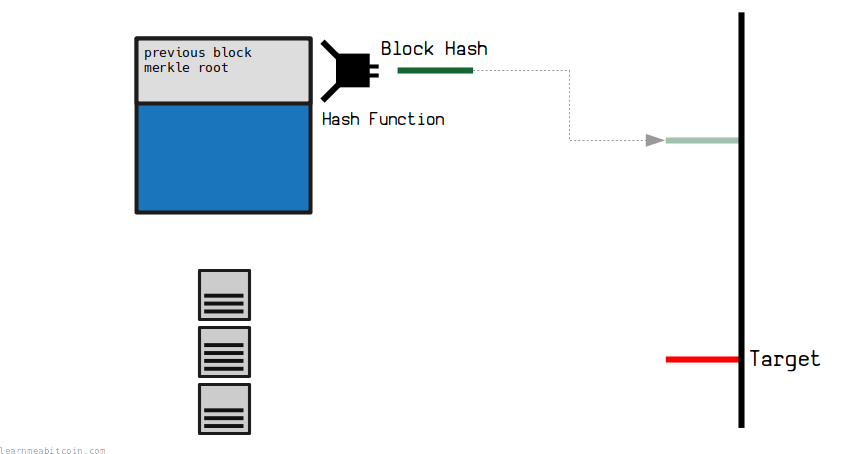

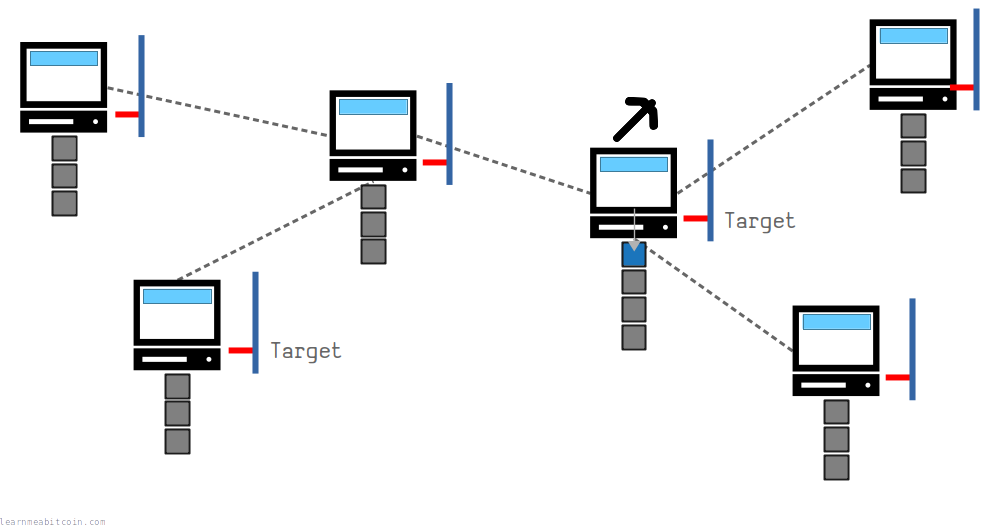

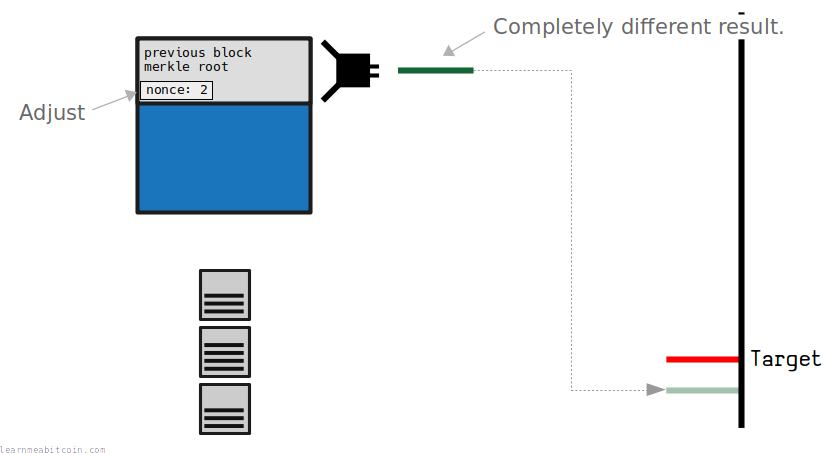

To do this, we put this block's block header through the SHA-256 hash function twice (called HASH256 for short), and hope that the number it spits out is below the current target.

If the hash of your block header isn't below the target, you can keep trying by incrementing the nonce field in the block header. This allows you to keep the same basic block header, but get a completely different hash result for it.

And if you're lucky, you may end up getting a block hash that's below the current target.

Synchronization

How do nodes update their blockchain?

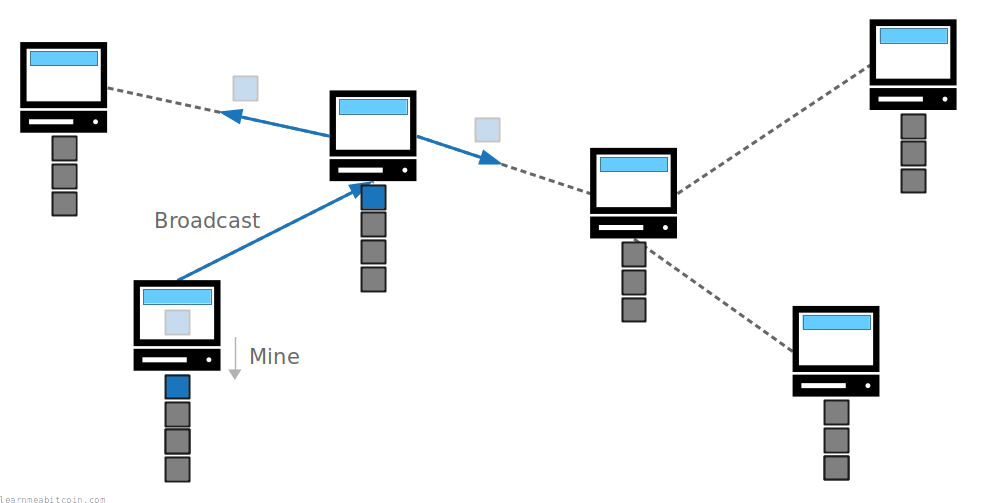

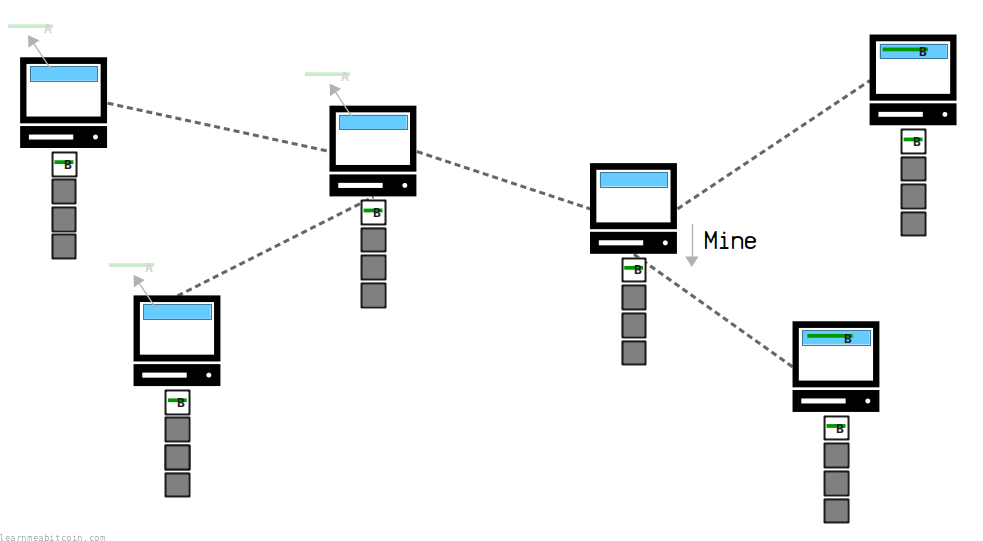

If a miner manages to get a block hash for their candidate block below the target, they will broadcast that block to the rest of network.

Each node will then confirm that the block header hashes below the target, then add this "mined" block on to their blockchain.

From here, each node will stop working on their own candidate block, construct a new one (with fresh transactions from their memory pool), and start trying to build on top of this new block in the chain.

As a result, miners are constantly working independently (yet collaboratively) to extend the blockchain with new blocks of transactions.

Proof of Work

What does proof of work mean?

The mining process is often referred to as proof of work.

The term "proof of work" just refers to the fact that it takes work to get a block hash below the target. And if you can, anyone else can check that work has been done by confirming that the hash for the block you have constructed is indeed below the target.

In other words, the hash function is used as a way to prove that you have performed a required amount of "work" on your block.

The proof-of-work involves scanning for a value that when hashed, such as with SHA-256, the hash begins with a number of zero bits.

Miners

Who can mine blocks?

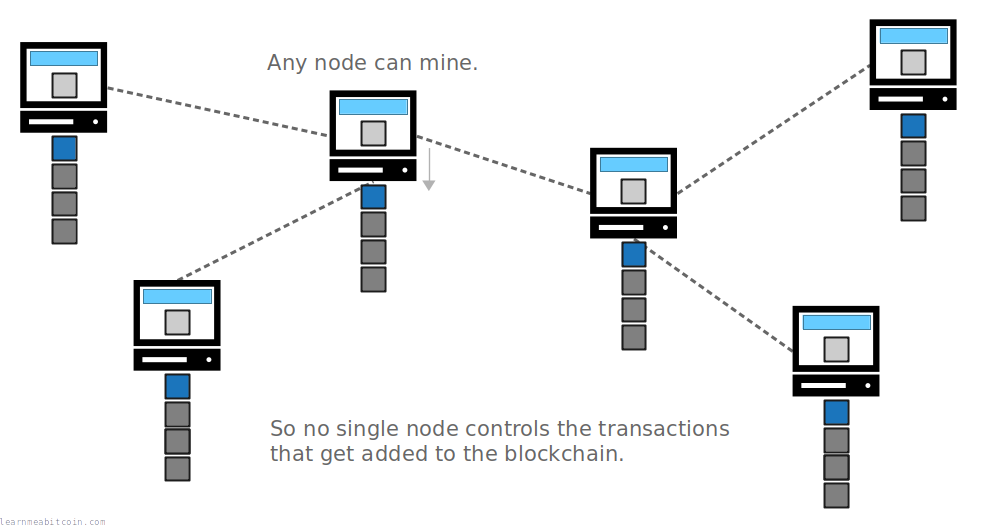

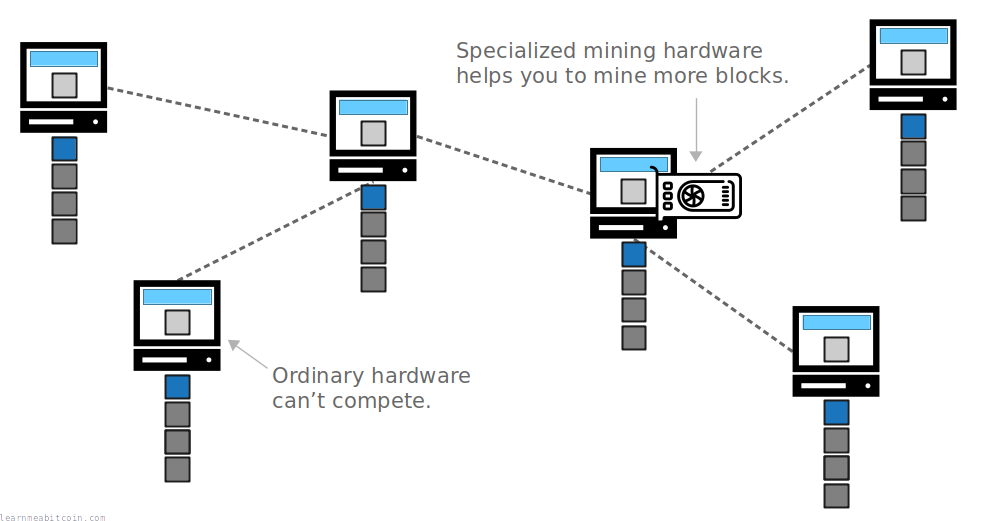

Any node can try to mine a block, and each node has a chance of being successful.

This means we have a network-wide competition where any node on the network could be the one to add the next batch of transactions on to the blockchain.

However, although anyone can try mining, being able to perform hash calculations as fast as possible improves your chances of successfully mining the next block.

Anyone's chance of finding a solution at any time is proportional to their CPU power.

As a result, miners with the most processing power (or "hashing power") are more likely to mine a block than those who cannot hash as quickly. So even though anyone can mine, it favors those with specialized mining hardware and access to cheap electricity to power that hardware.

But still, nothing is stopping you from mining if you want to.

Block Reward

What's the incentive to mine blocks?

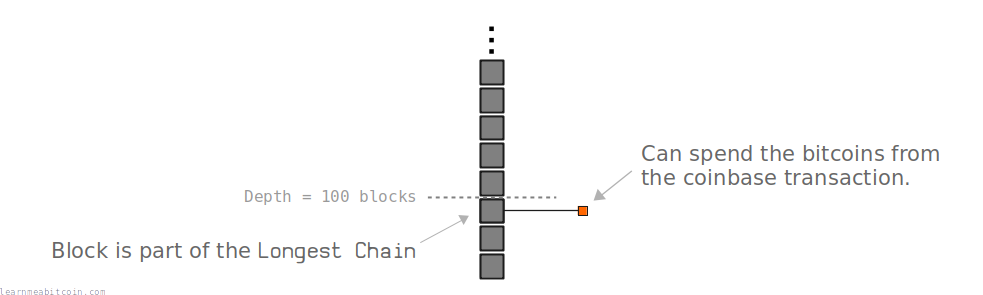

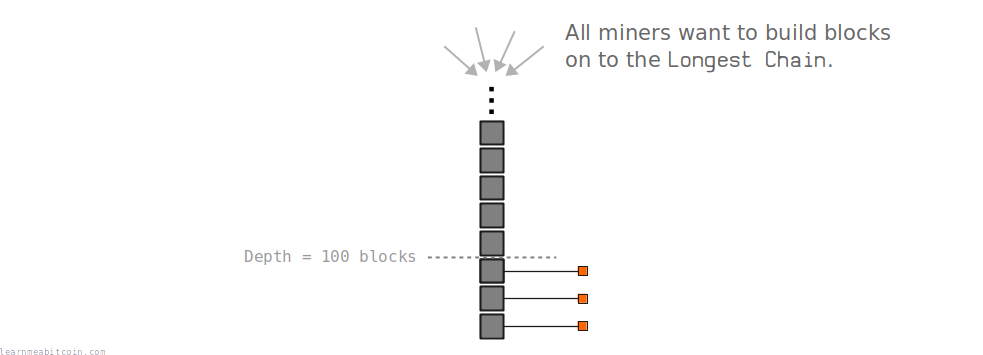

If you are able to mine a block you can claim a block reward.

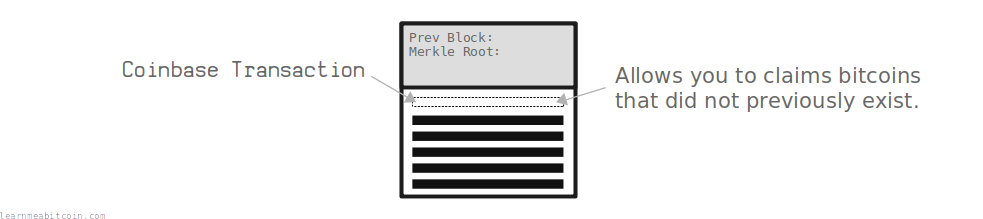

You see, when you construct a candidate block, you can put your own special transaction at the top of the block. This is called the coinbase transaction, and it allows you to send yourself a fixed amount of bitcoins that did not previously exist.

So if you end up mining this block, you would be able to spend the bitcoins you claimed from the coinbase transaction after the block reaches 100 blocks deep in the longest chain.

Therefore, this block reward acts as an incentive for miners to mine new blocks and continually try to extend the longest known chain of blocks.

- Sending bitcoins that did not previously exist is only allowed in the coinbase transaction. This makes the coinbase transaction the source of all new bitcoins.

- The presence of the block reward is why this process is called "mining". However, from a technical point of view, mining is mainly concerned with adding new transactions to the blockchain.

Interval

How long does it take to mine a block?

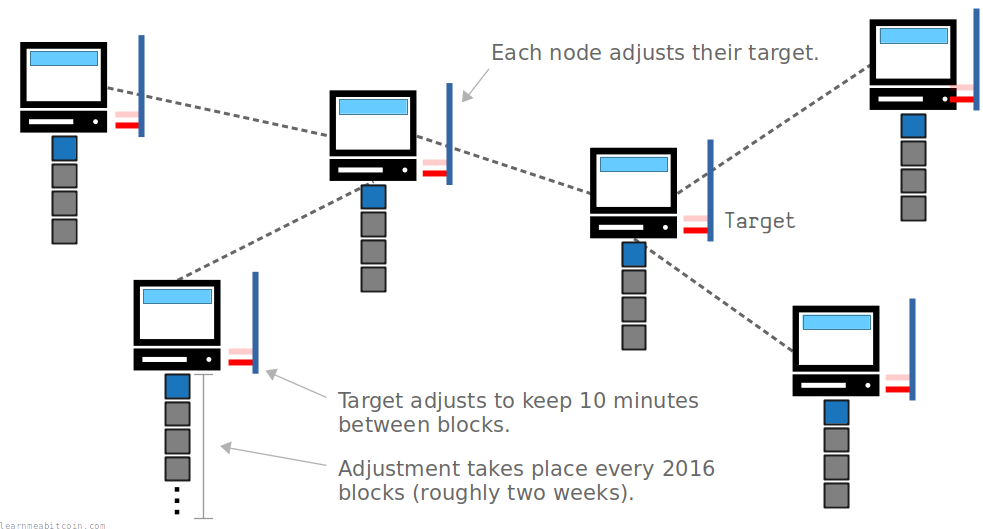

The mining system is designed so that one miner across the bitcoin network will successfully mine a new block once every 10 minutes (on average).

The timing is controlled by the target, which is like a limbo pole that a block's hash has to get under for the block to be allowed on to the blockchain.

If blocks are mined faster than 10 minutes on average over a two-week period (e.g. because more miners join the network), the target will adjust downwards so that it becomes more difficult to mine a block, and so the average time between blocks reverts back to around 10 minutes.

As a result, the target regularly adjusts to try and keep a regular interval of 10 minutes between newly-mined blocks. This enforces a consistent rate of new blocks, in addition to a consistent issuance of new bitcoins into the network.

Purpose

Why do we use mining?

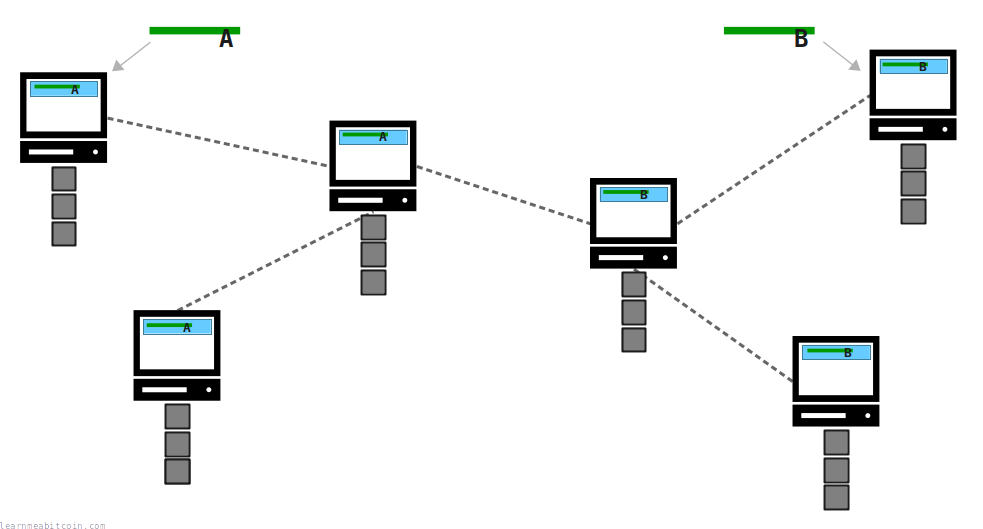

The mining system allows computers across a network to resolve conflicts without the need for a central computer to sort them out.

Bitcoin runs across a network of independent computers, so it's possible to create two conflicting transactions (sending the same bitcoins to different places) and insert them in to different nodes on the network at the same time. Some nodes will receive transaction A first, and other nodes will receive transaction B first.

But thanks to the mechanism of mining, only one of these transactions will make it into the blockchain.

Eventually, one of the nodes on the network will mine a block of transactions from their memory pool, and broadcast this block to the rest of the network. When nodes receive this block, they will add it to their chain and remove any conflicting transactions from their memory pool.

As a result, the process of mining acts as a sorting mechanism for transactions across a network of computers; the mined blocks have the final say on which transactions belong in the blockchain.

Better still, thanks to the fact that anyone can mine, no single node on the network is ever in complete control of which transactions make it into the blockchain.

A single miner can control which transactions make it on to the blockchain if they can acquire a majority of the mining power. This is known as a 51% attack.

Technical

How do you mine a block?

To mine a block, you start by constructing a block header for your candidate block.

For example, here's what the block header for block 100,000 would have started out like:

0100000050120119172a610421a6c3011dd330d9df07b63616c2cc1f1cd00200000000006657a9252aacd5c0b2940996ecff952228c3067cc38d4885efb5a4ac4247e9f337221b4d4c86041b00000000

Now you've got a block header, you try and "mine" it by putting it through HASH256. You keep incrementing the nonce value as you go to try and get a result below the target.

For example:

Nonce Hash256

-------- -------

00000000: 5bd0d617b30a972407ad69a845cd74fb201d940cd45acc15fcd4761493bc3ae2

01000000: 6879c316d8a96269825111bb0616331307bb6677b2af55127922d8c568e4b2db

02000000: 34d69cb489442234ec54462e18262bf1a9c756a4e7909e68edf979a0cb39a3fa

03000000: 8cf5e032093cfcbf4f6b443608631dd33699fca13dcbd6118992f9d451b70dd8

04000000: a32d73e3f2fd0579c44080cb6b1717582d37b8f47a8445922dee0996b503c04c

05000000: 70b11dabc90a107918a55eff7e940d41b0ce1924aeed2f0b7ccb2d4ee60e1617

06000000: b38afc30567703629226557a7748bea449693156e0b116b03a8442ccc3b9005e

07000000: 2a6008f39daa1238388eadcab111c6b556c3d89a46558c98f8ed32746fb5d7b8

08000000: 248e33c82a744786e7e16336612221850e32f8e6cb09b2eb0b0730ac6beb71b4

09000000: a4aea05d2750e49e8f95f5608293f6b4f45bd34aee51e86893dd8c0230d19185

0a000000: ce2225a69a5bf2dbb25cbb27fda78a8c4c3ac5280ec7996426eeefeb0e5e1ecb

...

Eventually you may find a nonce value that produces a hash result below the target:

Nonce Hash256

-------- -------

0f2b5710: 000000000003ba27aa200b1cecaad478d2b00432346c3f1f3986da1afd33e506

- The nonce is a 4-byte field in little-endian byte order.

- The result of hashing the raw block header through HASH256 will appear to be backwards at first. This is because block hashes are displayed in reverse byte order on blockchain explorers.

Code

Here's some Ruby code that shows how you can mine a block (like the one above).

The code is simpler than you might think. The only tricky part is getting the block header data in the correct format before hashing it.

Mining Simulator

copied

copied copied

copiedrequire 'digest/sha2'

# -----------------

# Utility Functions

# -----------------

# The hash function used in mining (convert hexadecimal to binary first, then SHA256 twice)

def hash256(data)

binary = [data].pack("H*")

hash1 = Digest::SHA256.digest(binary)

hash2 = Digest::SHA256.hexdigest(hash1)

end

# Convert a number to fit inside a field that is a specific number of bytes e.g. field(1, 4) = 00000001

def field(data, size)

hex = data.to_i.to_s(16).rjust(size * 2, '0')

end

# Reverse the order of bytes (often happens when working with raw bitcoin data)

def reversebytes(data)

data.scan(/../).reverse.join

end

# ------------

# Block Header (e.g. block 100,000)

# ------------

# Target (optional)

target = '000000000004864c000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000'

# Block Header (Fields)

version = '1'

prevblock = '000000000002d01c1fccc21636b607dfd930d31d01c3a62104612a1719011250'

merkleroot = 'f3e94742aca4b5ef85488dc37c06c3282295ffec960994b2c0d5ac2a25a95766'

time = '1293623863' # Unixtime (29 Dec 2010, 11:57:43)

bits = '1b04864c'

nonce = 0 # 274148111

# Block Header (Serialized)

header = reversebytes(field(version, 4)) + reversebytes(prevblock) + reversebytes(merkleroot) + reversebytes(field(time, 4)) + reversebytes(bits)

# -----

# Mine!

# -----

loop do

# hash the block header

attempt = header + reversebytes(field(nonce, 4))

result = reversebytes(hash256(attempt))

# show result

puts "#{nonce}: #{result}"

# end if we get a block hash below the target

if result.to_i(16) < target.to_i(16)

break

end

# increment the nonce and try again...

nonce += 1

end

Commands

bitcoin-cli getblocktemplate

This command grabs transactions from your node's memory pool and returns the data you need to start mining a new block.

Annoyingly, you also have to provide an awkward array to specify the kind of block template you want (see BIP22). This is what I typically use: bitcoin-cli getblocktemplate '{"rules": ["segwit"]}'

This command returns the key block header information like the previous block, time, and bits, but you will need to construct the merkle root yourself.

bitcoin-cli submitblock [hex]

Send a raw block into the network.

For example, this is the genesis block:

$ bitcoin-cli submitblock 0100000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000003ba3edfd7a7b12b27ac72c3e67768f617fc81bc3888a51323a9fb8aa4b1e5e4a29ab5f49ffff001d1dac2b7c0101000000010000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000ffffffff4d04ffff001d0104455468652054696d65732030332f4a616e2f32303039204368616e63656c6c6f72206f6e206272696e6b206f66207365636f6e64206261696c6f757420666f722062616e6b73ffffffff0100f2052a01000000434104678afdb0fe5548271967f1a67130b7105cd6a828e03909a67962e0ea1f61deb649f6bc3f4cef38c4f35504e51ec112de5c384df7ba0b8d578a4c702b6bf11d5fac00000000This is a complete raw block. It must include the block header, the transaction count, and all the raw transaction data.

bitcoin-cli getmininginfo

This command returns some interesting mining information.

For example:

$ bitcoin-cli getmininginfo

{

"blocks": 939328,

"currentblockweight": 3999523,

"currentblocktx": 1321,

"bits": "1701f303",

"difficulty": 144398401518100.9,

"target": "00000000000000000001f3030000000000000000000000000000000000000000",

"networkhashps": 9.40712200955021e+20,

"pooledtx": 23075,

"chain": "main",

"next": {

"height": 939329,

"bits": "1701f303",

"difficulty": 144398401518100.9,

"target": "00000000000000000001f3030000000000000000000000000000000000000000"

},

"warnings": []

} If you run bitcoin-cli getblocktemplate beforehand it will also show you how many transactions from the memory pool are currently being included in the next block (under currentblocktx).